Charting Rugby’s early growth with a tale of Toms

The game of rugby's emergence into the sport we know and love today grew on the games field of Rugby school, influenced by the values that were paving the way for the British across the world.

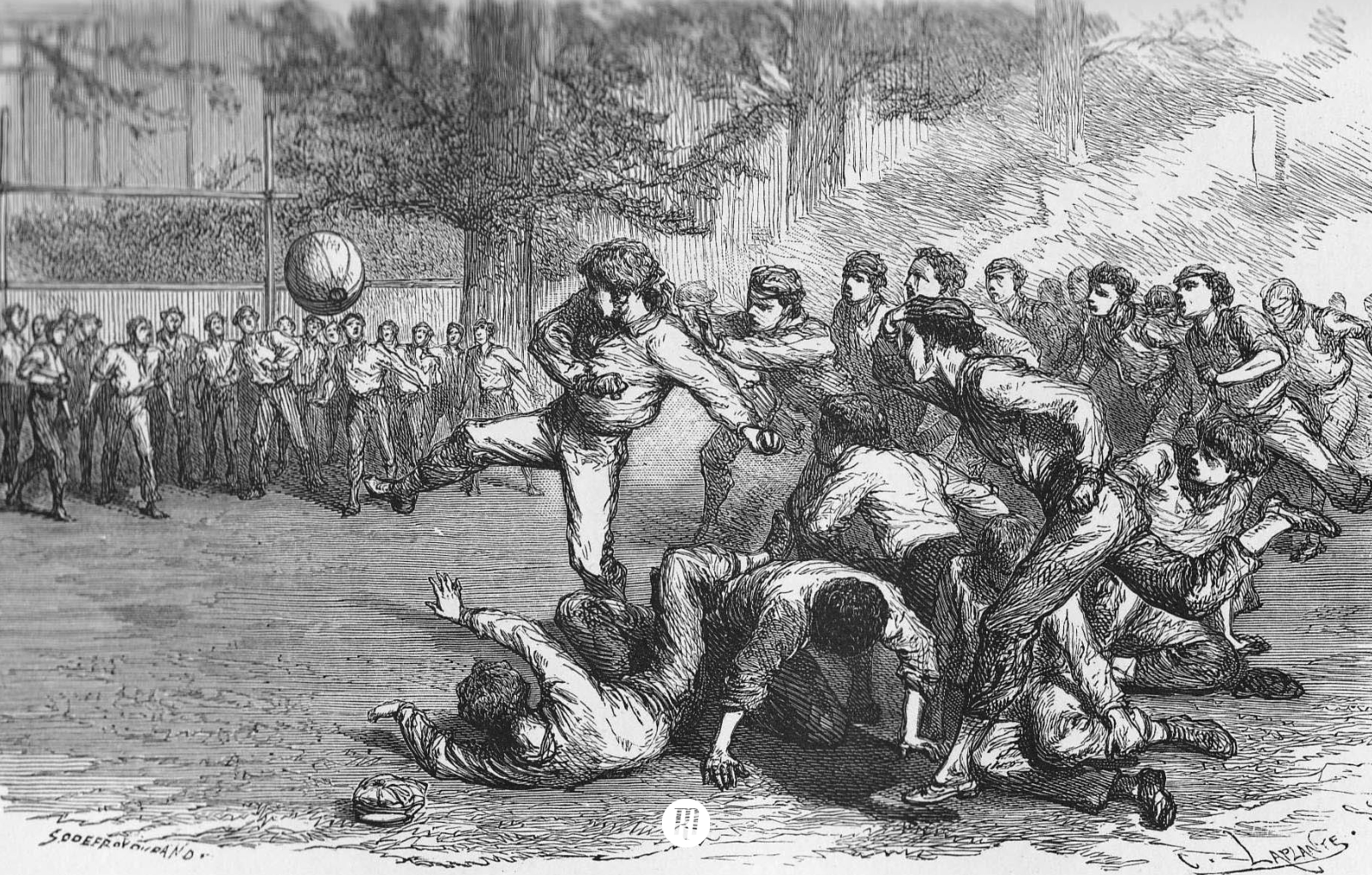

After the rebellion at Rugby school of 1797, games in rural schools across Britain started to flourish. While violent and aggressive, they were also controlled, and channelled young boy’s energies into an organised and safe environment.

However the game at Rugby School became about more than this, and especially under their headmaster from 1828 to 1841, Thomas Arnold. He was an advocate of Muscular Christianity, a philosophical movement that was characterised by duty, manliness, athleticism, teamwork and discipline.

Arnold himself believed in looking after your fellow man, team spirit, physical contact, hard work, and a sound christian moral upbringing. This Muscular Christianity was also paving the way for the British across the world, where her leaders were characterised by a competitive spirit to increase her bounds; and where better to learn these values than on a games field?

Arnold’s ideals were spread further with the publication of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, and for anyone who has read the book, you will certainly have a good impression of the game played at Rugby School, and the imposing figure Arnold himself casts over the story.

The novel was written in early 1856 by Thomas Hughes, a former pupil, for his eight-year old son, Maurice, to show what he could expect when he followed in his fathers footsteps.

The aim of Hughes in writing the book was to instil the importance of character, gentlemanly behaviour, and the values that could be learnt from sport that had been such a strong influence on his time at the school. He wanted the story to be educational, but entertaining at the same time. It was a huge success, and remains popular across the world.

The game of football during his time was not organised by the masters at the school though; it remained within the remit of the pupils. Where there were rules, they remained flexible, and changed each year with the new intake of boys. Different schools too, would have their styles of football, each passed down by word of mouth year on year.

Initially however, these games differed little from the games that had been played across England for centuries.

While the number of players was unlimited, there would usually be anywhere between 40 and 60 on each side, and there was no time limit either, with the winners being the first to score two goals.

This is highlighted, amongst other parts of the game, in the following extract from Tom Brown’s Schooldays:

“Tom followed East across the level ground till they came to a sort of gigantic gallows of two poles eighteen feet high, fixed upright in the ground some fourteen feet apart, with a cross-bar running from one to the other at the height of ten feet or thereabouts.

"This is one of the goals," said East, "and you see the other across there, right opposite, under the Doctor's wall. Well, the match is for the best of three goals; whichever side kicks two goals wins; and it won't do, you see, just to kick the ball through these posts; it must go over the cross-bar; any height'll do, so long as it's between the posts. You'll have to stay in goal to touch the ball when it rolls behind the posts, because if the other side touch it they have a try at goal. Then we fellows in quarters, we play just about in front of goal here, and have to turn the ball and kick it back before the big fellows on the other side can follow it up. And in front of us all the big fellows play, and that's where the scrummages are mostly."

Tom's respect increased as he struggled to make out his friend's technicalities, and the other set to work to explain the mysteries of "off your side," "drop-kicks," "punts," "places," and the other intricacies of the great science of football.”

So it is clear at this time that kicking the ball over the cross bar was an important aspect of the game, and indeed as is the custom with football today, only goals counted towards the score. This extract also highlights some of the classifications we use for specific events in today’s game: the most iconic of which is ‘a try at goal’ for touching the ball once over the goal line; but there are scrummages in there, and some semblance of positions and names for different types of kick.

There were also other aspects in the game that Thomas Hughes played in his time at the school that remain today. When a try at goal was scored, the player who scored would kick the ball back to a fellow team mate directly behind him on the field of play. If he caught the ball and made a mark, he was allowed to place the ball and kick for goal, but at the same time, the opposition were allowed to charge at him from their own goal line. Charging is still allowed for conversions, though with so many players rushing at you to avoid conceding a goal, it is no wonder that the pupils at the school changed the rules to kick the ball over the posts and not through the goal.

Despite this extract sounding rather similar to the game we enjoy in our time, there were still many differences - matches tended to consist of scrummages for the most part, though not as we know them today. With any number of people allowed to join, and standing and pushing rather than packing down, the aim was to dribble the ball forward with the scrum, and over the opposition try-line; hooking it back out of the scrum was considered cheating!

There are other key features of today’s game that come out of this time; players of each house were awarded caps in order to differentiate one from another, and this is why caps are awarded in today’s international fixtures. It’s also worth noting that Rugby’s schoolboys wore white jerseys, and this was picked up on as a tradition for the first international fixture England played in, hence their white kit.

Whether one could run with the ball in hand remained debatable even in the early 1830s, though it grew through this decade and was eventually popularised by ‘the great runner-in’ Jem Mackie. He was expelled from the school after an unspecified ‘incident’, but had he not been, perhaps he instead of William Webb Ellis might have been considered the founder of Rugby Football?

Thomas Harris, the previously mentioned contemporary of Webb Ellis, pointed out to the 1895 inquiry that running with the ball in hand was absolutely forbidden during the 1820s.

Thomas Hughes is quoted as saying to the inquiry, “In my first year, 1834, running with the ball to get a try by touching down within goal was not absolutely forbidden, but a jury of Rugby boys of that day would almost certainly have found a verdict of 'justifiable homicide' if a boy had been killed in running in.”

Further to this, a pupil by the name of J.R. Lyon, at the school during the 1830s indicated that it was allowed if the player could withstand the bombardment of hacking and collaring.

Hacking was simply kicking another player in the shins, and it would become an important and controversial discussion point as the game evolved. Indeed, it feels as though the game at this time was little more than showing one’s ability to give and take a hack. This of course was extolled by the Victorian principles and Muscular Christianity of the time - it was the greatest test of manliness.

By the late 1830s, word of mouth was no longer efficient as a means by which to pass on the rules of the game, and so in 1845, the Rugby School game of football had its first set of written rules. Those chosen to draft the rules were William Arnold, the son of the now deceased former headmaster, and W.W. Shirley, who would go on to become a professor at Oxford University.

Their rules were far from precise, and only really covered off certain areas that were often disputed, leaving the rest to the already available knowledge of the Rugby schoolboys. It would however define the important concept of offside, as well as indicating that all matches are drawn after five days, or three if there is no score. Clearly no one was in a rush for decisive results - assumably it was lengthy games or school work?

Eton would follow suit, drafting their rules in 1849, followed shortly after by Shrewsbury in 1855, Westminster in 1860, and Charterhouse in 1862.

The same issues were being raised beyond the school at universities as well, where ex-pupils came head to head with the varying forms of football played by other schools across the country. One ex-Rugbeian called Albert Pell, desiring to start a football club at Cambridge in 1839 was disappointed when a set of rules could not be agreed upon.

This permeation of the Rugby code was not just spreading to universities with ex-pupils, but in other ways too, with Marlborough adopting Rugby football in 1852 when an ex-Rugby headmaster joined the school. Clifton also picked up the code when an ex-Rugby pupil became its headmaster. Other schools would pick up the Rugby game too, inspired by its roots in the virtues of muscular Christianity, and almost always to the extinction of their own.

The further spread of the game was helped in no small part by the publication of Tom Brown’s Schooldays and the many ex-Rugbeians that turned the sport into an adult pastime.

It is sad to say however, that the young boy for whom Tom Brown’s Schooldays was written would never get the opportunity to either read it, or play the game that is so reverently described within its pages. Maurice Hughes would pass away two years after the book was published.

The varying styles and disparity of rules would be accentuated by the rapid growth of football through the middle of the 19th century, and would eventually come to a head. Football as a whole would be challenged, and but for the desires and decisions of certain individuals and clubs, our sporting landscape could be quite different...

Filed under:

Historical Series

Written by: Edward Kerr

Follow: @edwardrkerr · @therugbymag