What tactical variations did we see in this Rugby World Cup, which ones might we see more of in the future, and why?

From a tactical point of view, a world cup is always fascinating. The combination of pool and knockout games, the potential for an underdog upset if you over-rotate, the likelihood of playing a side that you are less familiar with, the squad constraints, and the sheer pressure of the global stage all combine to make a brilliant display for those who like to think about tactics.

This is true of a global tournament in any sport, really, but Rugby World Cup 2019 gave us a series of tactical battles interesting and important enough to have made it an instant classic of the genre. What were the most interesting of those tactical variations and will any influence domestic and international rugby during the next cycle?

Playmaker 15s

This was probably one of the most noticeable tactical selection policies at the world cup because such high-profile teams employed it. Both England and New Zealand dropped established, traditional fullbacks for a creative option in attack. Beauden Barrett, of course, started his test career mostly at 15 and New Zealand had been using Damien Mackenzie in the same role before his injury. Doing so gave them even more flexibility in attack, as Ali Stokes wrote at the time.

England opted for Elliot Daly, an outside centre by trade with a lot of experience as an international wing and a gifted, versatile player – although arguably without the instincts of a natural fullback. Daly worked to improve his high ball skills and defensive positioning and, while he was occasionally exposed, he offered more than enough in attack to keep the spot. His intelligence, passing ability, and linkwork gave England a third playmaking option (because there were usually two of George Ford, Owen Farrell, and Henry Slade on the pitch as well), ensuring they were always a threat in attack.

Of course, some teams, like Scotland, have long had a playmaker offering a threat from this position. But it was noticeable in this RWC just how many sides asked their 15 to be a playmaker – even South Africa, the supposed arch-pragmatists, used Willie le Roux’s creativity at times. This option tends to demand a trade-off between attacking threat and defensive stability but adding more playmaking vision to a side’s attack, especially as defences get increasingly difficult to break down, definitely has rewards. It’s probably an approach we will see more of.

Double opensides

This tactic got star billing at the last RWC, although it wasn’t technically new then, either in the modern game or before. However, the success of Australia’s “Pooper” combination, which took them all the way to the final, caught the headlines at the time and, in 2019, they weren’t the only ones who went for it.

The twin openside approach, done correctly, gives you more of a threat at the breakdown, allowing teams more chance of slowing down of snaffling opposition ball, as well as more chance of securing their own. It’s easy to see the appeal. England, who have long suffered from the lack of a proper openside, suddenly found themselves with two excellent options at the same time and, with them both fit, went for it. Tom Curry and Sam Underhill emerged as two of the stars of the tournament.

Australia again selected Michael Hooper and David Pocock, although this time the latter was asked to play at No6 rather than at No8, where he had featured in 2015. This gave Australia more ball-carrying options but, somewhat ironically, reduced Pocock’s effectiveness as he found himself doing the dirty work of a blindside at the breakdown rather than capitalising on it.

The double openside approach has a significant impact on your pack, meaning it only works with certain players. It tends to reduce both your carrying and lineout options. Wales, who have often played with two opensides since 2013, have been able to do so because Justin Tipuric, usually at 7, is an excellent lineout jumper, while Sam Warburton and Josh Navidi, his usual blindside partners, devoted themselves to tackling and carrying to compensate.

England, for instance, asked Curry to work on his carrying and jumping to make the partnership more effective – with great success. New Zealand, who have some of the best lineout operators in world rugby, played Ardie Savea and Sam Cane as twin opensides by asking Kieran Read to take on much of the duties of a blindside and free his flankers up.

This option has been a trend at club level for a while and we will almost certainly see more of it. However, the benefit of two opensides needs to be carefully balanced against the cost to the pack. In fact, a traditional blindside is often the glue that holds a team together – unflashy but integral.

In fact, this leads into our next tactical approach...

The old school is the best school

Which team won this world cup? South Africa? How did they do it? By going back to the basics. It doesn’t matter how talented your backs are, they will always struggle without a platform from the forwards. And, if your forwards are good enough, sometimes you can do without the backs. That’s how rugby started out, after all.

There was not much that was subtle about South Africa’s game plan, even if the two tries they scored in the final were lovely displays of attacking talent. Not only did the Springboks go for a 6/2 split on the bench, allowing Rassie Erasmus to replace his entire tight five once they’d emptied the tank, but they selected Frans Steyn in the 23 jersey, the type of back that the forwards probably wouldn’t mind joining the scrum. And that was on top of selecting Handre Pollard at flyhalf, a man they almost used as a forward at times. Calling it physical would be an understatement.

But this wasn’t just a case of brute force. For all that Pieter-Steph du Toit haunted Ford’s footsteps in that final and Pollard took the ball into contact, the Boks were savvy about how they used their physicality. Pollard took the ball into contact often enough to keep England guessing when he didn’t. He appeared in the forward pods during a phase attack to surprise England and release his backs. Damien de Allende spent the tournament smashing through defenders and then, after one warning run at Ford, was used as a decoy throughout the final.

In fact, the South African pack that started against England was a full 20kg lighter than their opponents. They just knew exactly how to use their weight and their technical ability. As Squidge Rugby observes, the midfield maul they set up to earn Pollard a chance to kick at goal played on the fact that their lineout had been a major strength before taking the simplest option and passing to the front, allowing their forwards to set up for the maul.

This was old-fashioned rugby, coached intelligently, and executed perfectly. However, it needs physical players and the brains to exploit their ability so its use as a tactic might be beyond a lot of teams. South Africa could easily keep using it, though, because – as we saw – it’s very hard to stop.

Interchanging centres

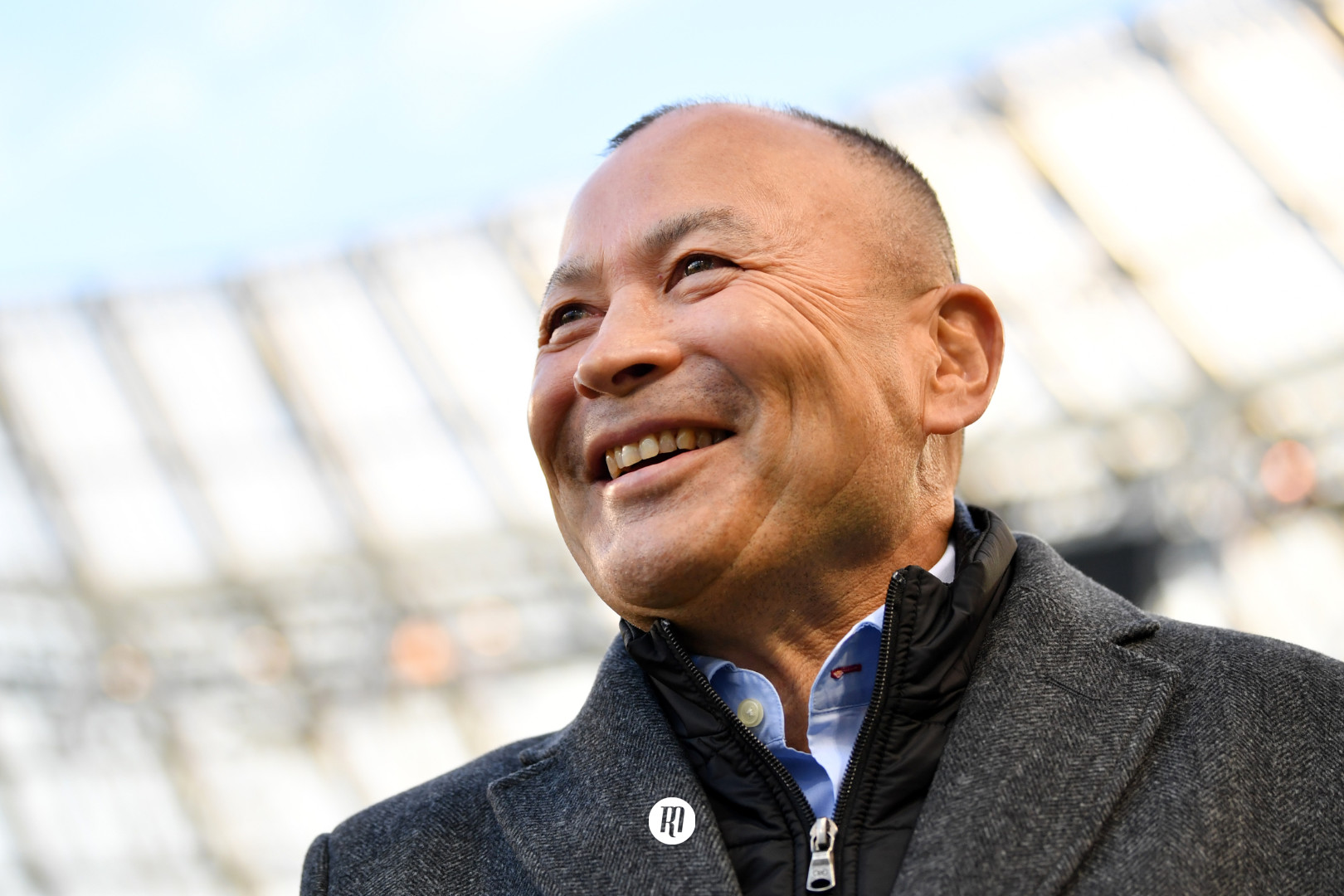

This is another approach that is not exactly new but it was interesting to see just how many teams used it in this tournament. England are big fans of tactical variety under Eddie Jones and, in addition to twin opensides and a playmaking 15, they also occasionally used this tactic (when they weren’t playing two flyhalves, that is).

Some centres are more natural No12s, some are more comfortable at 13, and some are at ease in either position. Australia, England, and France all asked their centres to chop and change position according to the needs of the team in attack and defence. Against Wales in the second half, Australia moved James O’Connor in from 13 to be a second distributor as they chased the game.

In their crucial opener against Argentina, Virimi Vakatawa wore the French 12 jersey and Gaël Fickou wore 13 but the two swapped around with ease, combining beautifully to score France’s first try. England, meanwhile, often got the most out of Manu Tuilagi by using him to defend the 12 channel but attack the greater space offered as a 13, with Slade stepping into the 12 position to create chances for his fellow centre.

Early on in the 2013 British and Irish Lions tour, as speculation raged about who would start in the centre positions, Brian O’Driscoll observed that centres had to be comfortable switching between the two. In his column at the time, he added, “I have always switched between 12 and 13. Predominantly I have defended at outside centre. For certain plays, I have switched in.” This tactic, which allows teams the best of both worlds in midfield, isn’t going anywhere.

The less successful options

There was plenty more, of course, in playing style as well as selection. Fiji coach John McKee got the most out of his players’ sevens expertise by adapting traditional attacking structures to suit their strengths. Japan delighted fans everywhere with their lightning fast phases and changes of direction from the ruck. Uruguay picked up their (surely already immortal) victory over Fiji with an old-fashioned approach, tackling themselves to a metaphorical standstill and then literally getting up to tackle again.

But some were less successful – and there were plenty of tactical takeaways there too. Australia were determined to run the ball wherever possible rather than kick, to their eventual detriment. Ireland’s possession-heavy game plan also suffered in the humid conditions, while Scotland’s fast-paced approach suffered against both heavy carriers and the even faster style of Japan. Argentina’s efforts to play a more attacking game plan suffered when their forwards had neither the grunt nor the discipline to give them the platform they needed.

All in all, this Rugby World Cup had an engrossing variety of tactical options, quite a few of which we are likely to see more of. Is the best way to combat all this innovation to make like South Africa and commit to the traditional approach? It certainly was this time, as they defeated the tactical variation kings. But there’s always next time...

Filed under:

International, Rugby World Cup, Australia, England, France, Georgia, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Scotland, South Africa, Wales

Written by: Rhiannon Garth Jones

Follow: @@rhigarthjones · @therugbymag