What’s in a number?

An intriguing question recently reared its head, one that asked if a certain player can play in a given position; the answer goes to show just how tactically in depth this game really is.

Perhaps this question is asked more of international fixtures than club fixtures by virtue of the increased exposure, as well as pressure, the teams are under. It is a question that seems to raise its head more often than not, and one that shows rugby’s ever increasing tactical nature.

The catalyst for this article was a question that asked whether a certain player can play in a given position; similar to when people questioned Chris Robshaw at seven for England, or Owen Farrell in the centre. Other players across the world switch in and out of positions, to some extent regardless of whether they can play there or not.

Indeed this weekend, Finn Russell will start with a 12 on his back for Scotland. While he has played at 12 before in his career, to isolate the player and the position in such a fashion is to misunderstand how the game of rugby is evolving.

As a sport, rugby is about managing, manipulating and controlling space, be that with skill, pace or strength. This is similar to both Association and American Football; yet it is neither at the same time. Where American Football plays through phases, with play books as deep as your fist, Association Football is much more fluid, constantly in a state of flux.

Rugby sits comfortably in between. Whether from a scrum or lineout, rugby starts in the same place as American Football, and allows for similar plays, but from there, its nature shifts to that of Association Football; fluid, allowing the players to play what they see in front of them. There are of course still structures within this open play, but the onus is on the players to read and understand the situation, and react accordingly.

This then highlights why the number on your back becomes moot.

Once play has become more fluid, control of the space is in the hands of the players. Those players on the field however, will fit into the overall attacking threat the coach believes will break down the opposition, for which they would have picked accordingly.

In England’s case, the selection of Farrell along with Ford allowed the team to retain arguably their best game manager, alongside one of their best playmakers. Their selections though, were predicated on England’s focus at maintaining two man rucks, and delivering quick ball. This system saw pods of two forwards alongside Ford and Farrell, that offered screening runs, or options for carrying into contact.

Once this system had been found out and compromised, especially by Scotland in the 2018 Six Nations, England moved to increase the numbers at ruck time. As a result, this drew the forwards tighter, bringing them towards something akin to a three player pod setup (though if you watch closely, one of the second pod perhaps appears to have a slightly freer role). The impact of this on England’s shape has brought around two needs.

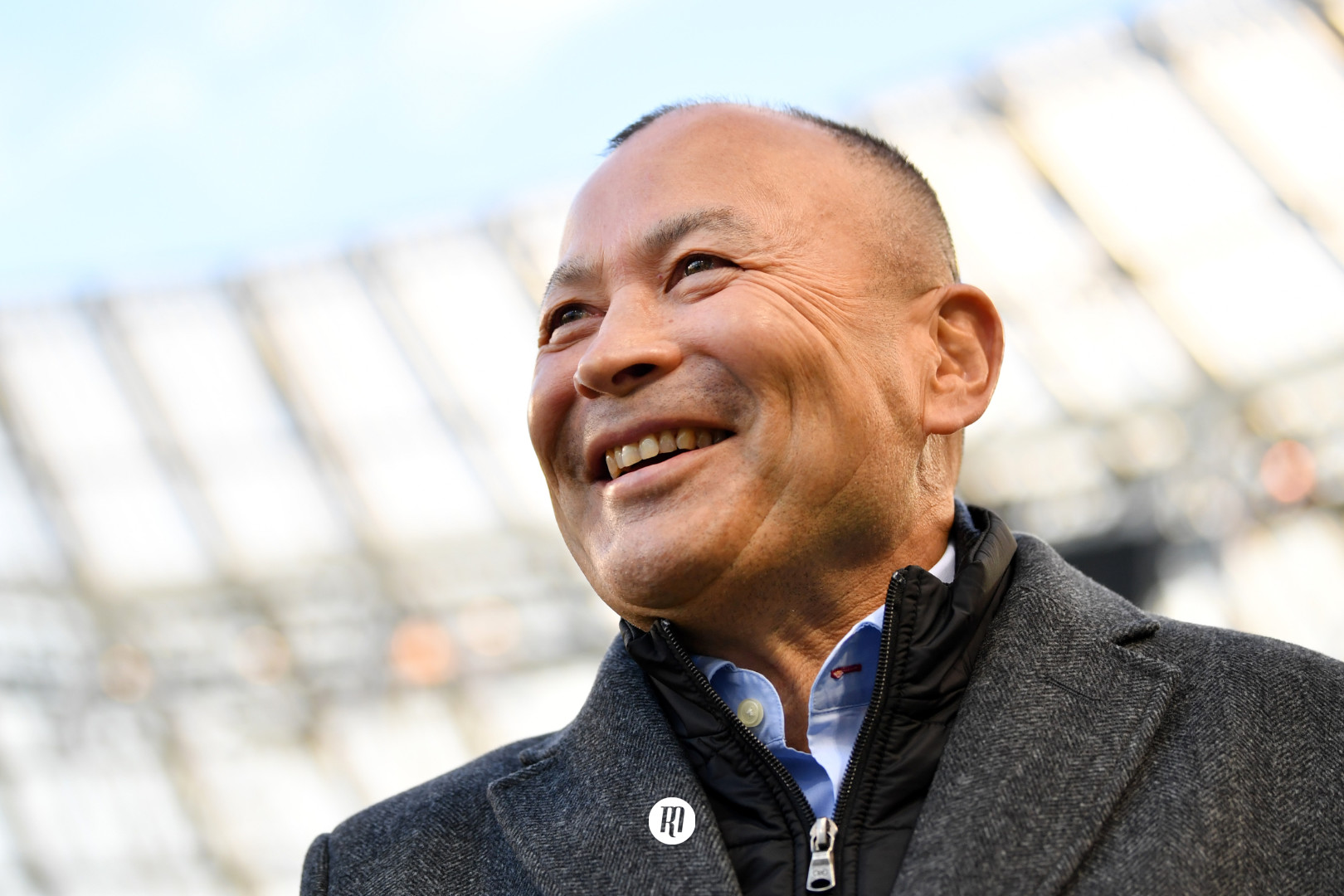

Eddie Jones has noted on several occasions that England’s backline is not the largest, and by increasing the number of forwards in each pod, the physical impact of the side has been decreased in the wider channels. This puts an onus on finding a player capable of taking the game to the opposition in the wider areas. Against Japan, that player was Jack Nowell, but it seems likely that this is a role that is waiting to be filled by Manu Tuilagi.

Futhermore, this shift pulls England’s playmakers in tighter, with Ford and Farrell, or indeed Farrell and Slade against New Zealand, sitting alongside the forward pods. This then leaves little playmaking ability in the wider areas, which goes a long way in supporting the selection of Elliot Daly at fullback. This is a player who regularly plays in the centre for Wasps, but the position he fills for England at fullback is remarkably similar to that filled by his club colleague Willie le Roux. Indeed England’s attacking structure has shades of Wasps running through it. Last season, it was Cipriani and Gopperth as the central playmakers, with le Roux on the outside. The latter incidentally finished with the highest number of assists throughout the season.

The same thought processes will have been running through the head of Gregor Townsend for Scotland; Adam Hastings has proven himself a consummate playmaker since making the switch to Glasgow, and with Stuart Hogg already established in the attacking mould that Elliot Daly is beginning to bring to England, it comes as little surprise that Finn Russell has been chosen to act as the intermediary playmaker.

The important point that each of these areas raises however, is that the structure of the team has (and needs) little resemblance to the numbers that are placed on the backs of players. Will a fit again Manu Tuilagi play alongside Ford and Farrell with a 12 on his back or a 13? Does Ben Te’o playing with a 12, and Henry Slade with a 13 alter their positions within the structure of the side? Of course not, they’re just numbers.

The same can be said of forwards to a point, though Jones’ experiment looks unlikely to appear again anytime soon; look at how Courtney Lawes and Maro Itoje have provided different roles for different situations, alternating their positions at the set piece as the need arises. Whether one wears 4 and the other 6, or vice versa, is moot; they have a job to do within the structure of the game plan.

And that is the key point; rugby is a game of structure and systems, and how players fit into and benefit that system is the core focus of those in charge. If that means a player has a number on their back that we don’t often see them wearing, the question is not whether a certain player can play in a given position, but what position has that player been given.

Filed under:

International, Match Analysis, Spirit Of The Game

Written by: Edward Kerr

Follow: @edwardrkerr · @therugbymag