1871: The First International

Scotland and England have provided some memorable fixtures over the years, but both teams contested the first rugby football international in 1871, shortly after the founding of the Rugby Football Union earlier in the year. Join us as we take a look at the game, and the impact it had on the growing sport.

1871 is an auspicious year for Rugby, not least because it is the year the first international match was contested, but also because it saw the creation of the first governing body within the sport.

In the December of 1870, two letters appeared in the London press; the first on 4th December was a letter to The Times calling on “those who play the rugby-type game” to meet in order to form a code of practice for the sport.

On the 21st of January 1871, the meeting took place, and representatives of 21 clubs went on to form the Rugby Football Union. There was one notable exception from the representation of the clubs; that of Wasps, whose delegate missed the meeting. There are multiple stories as to why this was the case, but the best is perhaps that having gone to the wrong venue, he decided that liking it so much, he would stay.

One of the key tactics in the sport up until this point, and certainly one of the more controversial was that of hacking, and as a result of this meeting, it was finally eliminated. Hacking would allow defensive players to bring the ball carrier to the ground by kicking their shins, as well as breaking up scrums in quick fashion, and it was a dispute over this rule that led to the schism in football and the founding of the Football Association. It was ironic then, that the final nail should be placed in the hacking coffin by the clubs who had withdrawn their membership from the Football Association as a result of the association’s decision to exclude it: Blackheath being at the heart of the growing football movement.

The second letter was published on the 8th of December, in both The Scotsman, and a London magazine called Bell’s Life, inviting the best footballers from England to compete against Scotland in a 20-a-side match of ‘Rugby-rules’.

This letter appeared shortly after a Scottish team had played against England in an association rules fixture, and it was felt at the time that the playing of association rules football did not accurately represent the footballing abilities of the Scottish people (there existed only four clubs playing association rules, with the majority of other clubs played ‘Rugby rules’); and incidentally, neither did they believe that Scotland was properly represented, with some doubts surrounding the selection of players for the Scottish team; it is said that one player was selected on nothing more than his penchant for whiskey.

It was then a Blackheath player (amongst many in the side) who would lead an England team against the Scots on the 27th of March 1871; Frederick Stokes would become England’s first captain, and would go on to become the president of the RFU three years later.

Stokes led his team up to Scotland on an overnight train to play two 50 minute halves at Raeburn Place, home of Academical Cricket Club in Edinburgh. Around 4,000 people turned up to watch the fixture, each being charged a shilling for entry; the gates would amass some £200, a grand sum in those days. Going into the fixture, Scotland organised a series of trial matches, in order to ensure that those players selected were an accurate representation of the Scottish game. This also ensured a great deal of excitement and eagerness for the fixture.

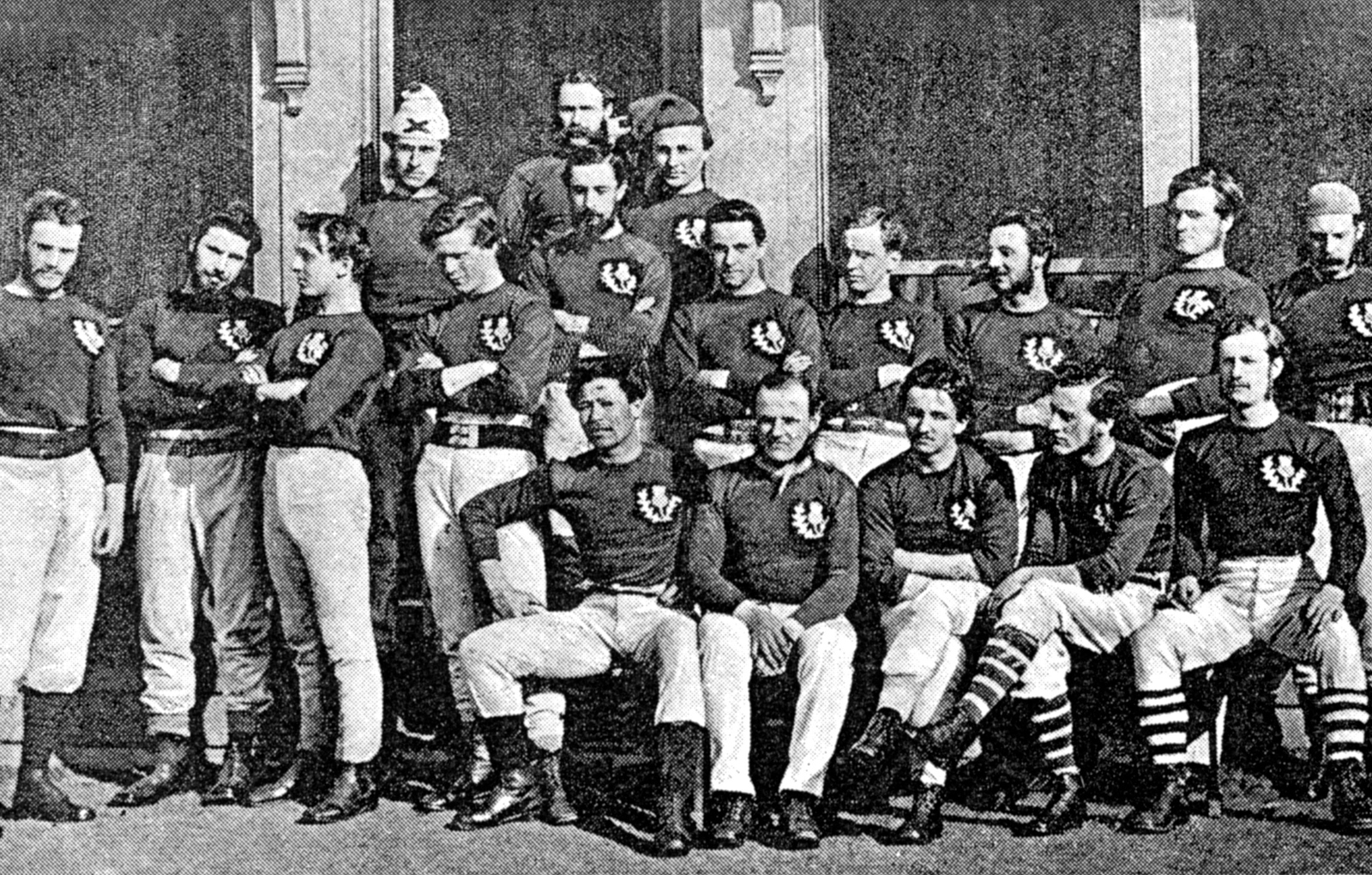

The Scottish team was led out by Francis Moncrieff, second son of Baron Moncreiff of Tulliebole, wearing brown shirts ornamented with a thistle, and cricket flannels. England played in all white, with a red rose on their chest. The game would be a great spectacle, though the predominantly Scottish crowd didn’t expect too much from their side given that the English appeared to be a lot heavier and stronger.

There was still a great amount of disparity between the rules that each team played under, and despite hacking having been removed, the English players still persisted with the tactic. After a dispute between the captains, with both unable to come to a decision, the referee, one Hely Hutchinson Almond, insisted he would walk from the field if hacking were allowed.

The game remained balanced throughout the opening stages, and by the time the first 50 minutes had drawn to a close, neither team had got over the finishing line.

It is worth noting that the rules for scoring at the time were very different to those we have today, but they do give us an indication of why some of the actions performed on the field have the names they do. A team would not receive any points for grounding the ball over the line, they would only give themselves a ‘try at goal’. The amount of goals, irrespective of the amount of tries a team scored would decide who won the contest.

When the second half began, the backs got into the game far more, and the ball moved from side to side. With some luck the Scots brought themselves up to the English line, and earned themselves a scrum. They drove forward, and Angus Buchanan, who also played cricket for Scotland, dived on the ball to score the first try in international rugby.

The driving of the scrum over the English line was illegal by the English laws of the game, and the English players vociferously argued that the try should not stand, however Almond gave the try, and Scotland earned the resulting ‘try at goal’, which was duly slotted by Malcolm Cross. Scotland took the lead at 1-0.

Almond would later say, "Let me make a confession: I do not know whether the decision which gave Scotland the try from which the winning goal was kicked was correct in fact. When an umpire is in doubt, I think he is justified in deciding against the side which makes the most noise. They are probably in the wrong.”

This however is where hacking as a tactic was perhaps at its most important: it allowed teams to break up scrummages. Should a scrummage not be broken up in this way, it was believed they would degenerate into long shoving matches, which no-one had an interest in seeing. Many backs might argue the same thing today.

England would eventually score a try of their own, their kick at goal falling short, before Scotland scored a second try during the closing stages of the game. This too was disputed; at a line-out close to the England goal line, one of the Scottish players accidentally knocked the ball on, before it was touched down by a Scottish player for a try. Under English laws, this knock-on was not allowed. By Scottish laws however, the knock-on was legal if it was not deliberate. Of course, this was a time when penalties were not awarded, as gentlemen did not cheat.

Despite the try being awarded, the kick at goal was missed and the game closed with Scotland becoming the first international victors, winning by one goal to nil.

Since this first international, England and Scotland have produced many memorable fixtures, and the two teams continue to contest the Calcutta Cup. The cup made its first appearance in the fixture of 1879, but as the sides drew, neither took the trophy home. Instead, England would become its first champions when they beat Scotland by two goals to one in 1880. Despite this being the case, the plinth on the bottom of the cup records the winners right the way back to this first international fixture in 1871.

The cup takes its name from The Calcutta Club, who after a handful of years playing rugby in a climate that many felt did not suit the sport, disbanded. At the time, and with a view to continuing the name of the club, the members withdrew the club’s remaining funds from the bank; these Silver Rupees were melted down and reformed into the Calcutta Cup. The club donated the trophy to the RFU stating that it should be contested annually, and it remains the oldest trophy in world rugby.

This first international would prove to be the catalyst for reform throughout the world of rugby; because teams at the highest level played each with greater frequency, a more centralised and coherent approach to the laws of the game was required. Many imitators to the RFU were created over the following years, and at the suggestion of the recently formed Scottish Football Union, tedious matches found a solution in reducing the amount of players from 20 to 15.

Around the same time, and while no points were earned, the value of a try increased such that if a game was drawn, the team who had scored the most tries would be declared the winner. Rugby had started its inexorable shift into the game we know today.

England would host Scotland for a return fixture in February of 1872, and the teams would continue to alternate as hosts annually. Ireland would join the two teams in 1875, before Wales completed the quartet of Home Nations in 1881, and so the Home Nations Championship, the precursor to the championship we enjoy today, was born.

Rugby itself has changed dramatically since this inaugural international fixture, but it was here that the seeds were sown for the future of the sport as a whole, and the game we enjoy today.

Filed under:

Six Nations, Historical Series, England, Scotland

Written by: Edward Kerr

Follow: @edwardrkerr · @therugbymag