How a boy named Astley was rugby’s real founder

The history of Rugby football has a mighty flag rising from the river of time that denotes its founding, held aloft by William Webb Ellis, but perhaps we are celebrating the exploits of the wrong person.

While rugby’s history holds a name and a date for its founding - William Webb Ellis, in 1823 - this event is apocryphal, brought forward by Old Rugbeians in the late 19th century, whose desire to maintain their weak grasp on the sport was loosening. Their inquiry in 1895 into the founding of the game resulted in the story of Webb Ellis being presented, and indeed they literally cemented their ownership on the game by issuing the famous plaque that now resides at Rugby School.

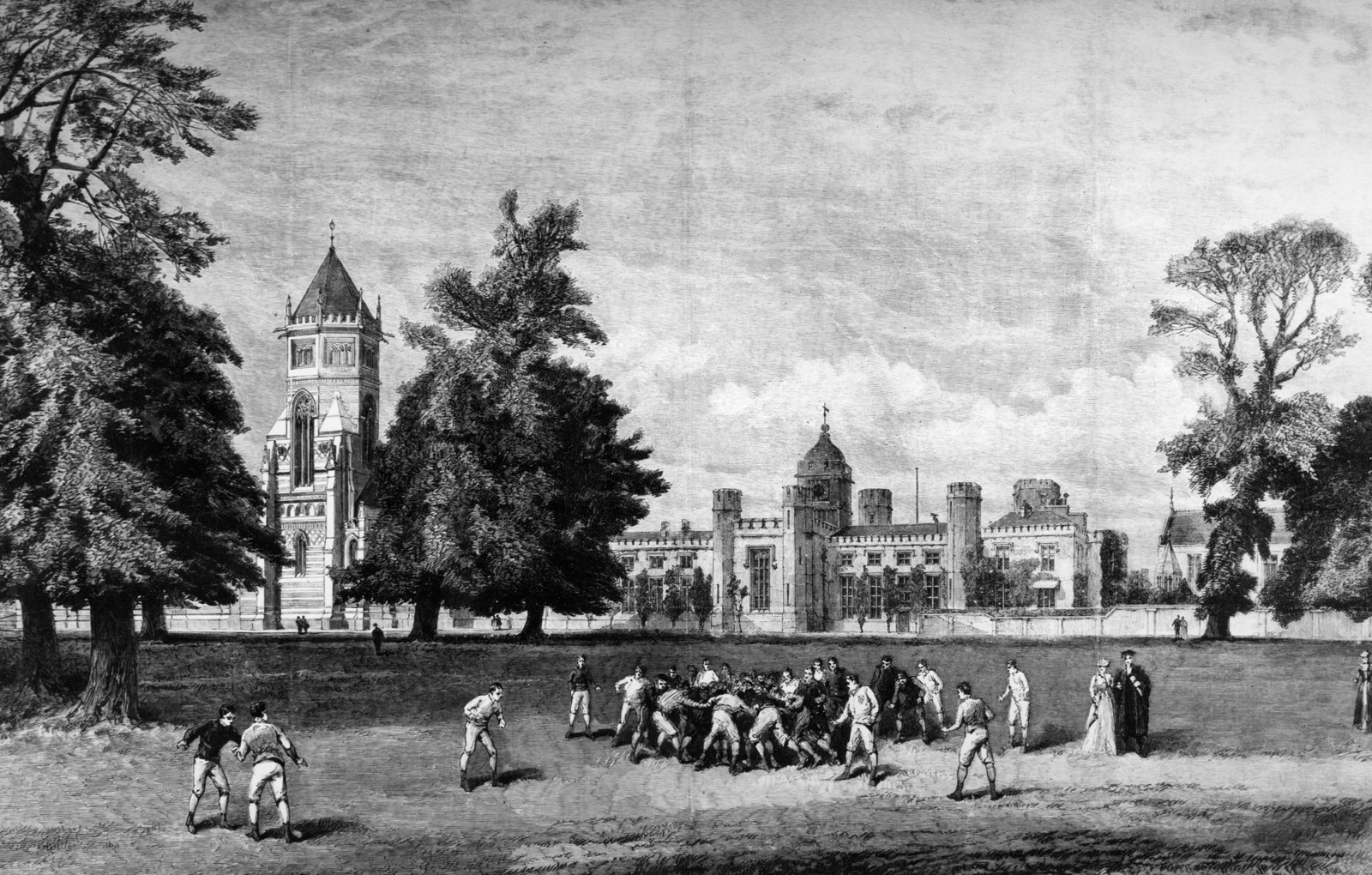

As tenuous as the story of William Web Ellis might be though, rugby football was undoubtably birthed at Rugby School.

However, the game had been conceived years before.

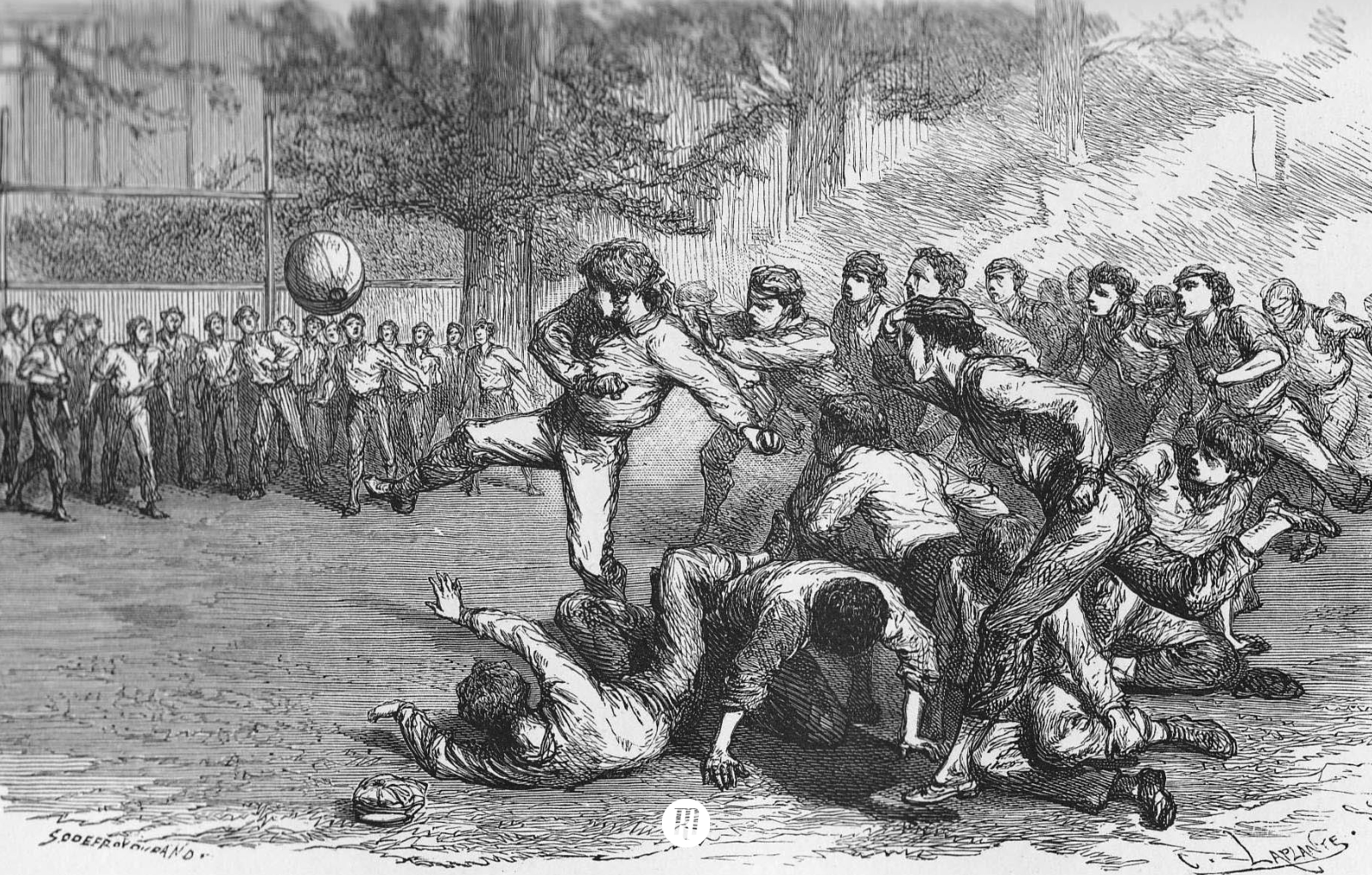

There have been varying types of game played across the world throughout history; the Romans played Harpastum; in Florence in the 16th century they played Calcio Fiorentino, still the name of association football in Italy today; in Cornwall, East Anglia and Wales they played a game that was very similar to one from northern France called La Soule.

Each of these games reflected what Rugby football would become far more than they did modern association football, and indeed, a game where one could only use one’s feet appears to be the exception to the rule.

By the early 19th century though, the popularity of these folk sports was slowly beginning to wane, as village society was turned upside down by industrialisation, and the movement of people into towns and cities. Even then, the stringent timings of being a factory worker ensured people were unable to put their time into sporting pursuits, and even if they could, the means of suppressing unofficial games were increased with the creation of police forces in 1829, and the Highways Act of 1835.

While these built up areas deprived people of a place to play their games, however, the reverse was true in rural public schools, where pupils had plenty of time, space, and energy. Games had been played in these institutions before the 19th century, but the widespread adoption of organised sport was driven by an altogether different influence.

Between 1768 and 1832, there were 21 recorded public school rebellions. These weren’t the sort of rebellions where one might get a detention; they were much worse…

In the year 1797, within the heart of the French Revolution, the continent was being torn asunder by a certain Napoleon Bonaparte, who during this year had brought eleven hundred years of Venetian independence to a close, as you do. Perhaps driven by this revolutionary fervour sweeping Europe, the pupils of Rugby School rose up against a tyranny of their own.

A boy named Astley was caught by the headmaster of the school firing cork bullets at the windows of local houses. Under interrogation, Astley said he had acquired the gunpowder he was using from a local grocer called Rowell. Conscious of being caught out, Rowell had entered the gunpowder in his records as sugar, before denying having sold it to Astley.

Astley was flogged.

Clearly a sense of injustice was kindled in the hearts of Astley and his friends; they proceeded to smash the grocer’s windows. The headmaster decreed that the 5th and 6th forms of the school should pay for the damages. Not happy with this perceived betrayal, Astley and his friends distributed flags around the school to unite all of the pupils, and furiously rang the school bell as a declaration of war.

They also somehow acquired a petard, an iron or brass bell-shaped device used by armies to breach walls or doors - one of those things lying around of course - and used it to blow open the door to the headmaster’s study.

They barricaded the corridors, and stripped the headmaster’s study bear, building a fire with his books and furniture. The pupils certainly chose the right time to stage the rebellion - most of the teaching staff were away from the school enjoying their weekend.

In his panic, the headmaster fell back to the only, and somewhat fortunate, resource available for quashing the uprising: an aptly timed recruiting party for the British Army happened to be in town. When news of the army’s arrival reached the boys, they retreated to the Bronze-Age burial mound that was within the school grounds, which at this time was surrounded by a six-metre wide moat, and drew up the drawbridge.

When the headmaster arrived at the drawbridge, he read the riot act in an effort to distract the boys while the troops approached the mound from behind, wading through the moat.

The rebellion was crushed, and the ring-leaders expelled. Incidentally, one of those expelled would later go on to be a general in the British Army, and another a bishop; the rest were caned into submission.

And so, this was the catalyst for organised sport within public schools - somewhere young boys could expel their pent up energy, in an environment that was controlled and safe for all of them (though I use safe lightly given some of the reports of early games I have read).

The boys at Rugby school would be playing their own version of a game that was developed from the foundations of the folk sports that had existed beforehand. Thus, in 1823, a young chap would catch the ball and set in motion a chain of events that would lead you to this article today.

Filed under:

Historical Series

Written by: Edward Kerr

Follow: @edwardrkerr · @therugbymag